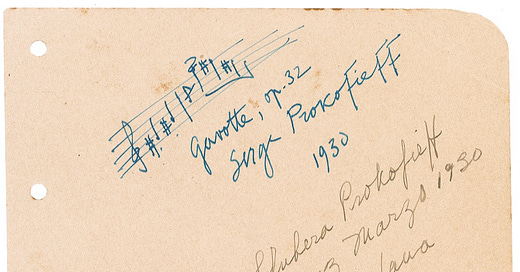

A Prokofiev melodic recipe

Many of Prokofiev's loveliest melodies have a simple structure we can emulate

Whenever I hear others talk about Prokofiev’s music, I most frequently hear about his harmonies and how brash and harsh they can be when combined with his unique style of orchestration. Years ago I remember leaving a Seattle Symphony performance of his 6th Symphony and overhearing someone saying the music left them cold—that it was too rough and wasn’t at all lyrical or melodic. That comment left me scratching my head wondering how we had had such different experiences. I had heard soaring tune after tune in the music—though frequently juxtaposed with more grotesque and brutal moods.

I still maintain that Prokofiev is one of the great melody writers of all time and that one needn’t look beyond the score for Romeo and Juliet for proof that he can turn out page after page of unique, memorable, and often very singable tunes. This fact can often be obscured by the other musical choices he makes that gives his music the special sparkle and twist that makes it his.

So I decided to comb through some of my favorite Prokofiev melodies to see what I could learn. Inso doing, I noticed a pattern emerging in many of them: Prokofiev frequently wrote scale line melodies (meaning they move stepwise along a scale) with the addition of a single leap (often upwards) in the first half of the melody. More specifically, I noticed two types of melodies that heavily rely on scales:

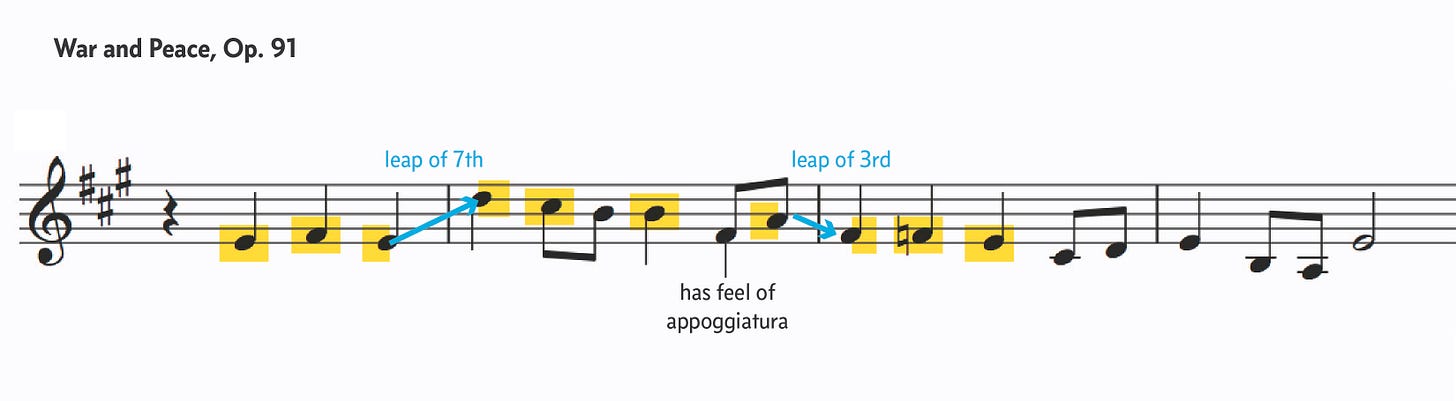

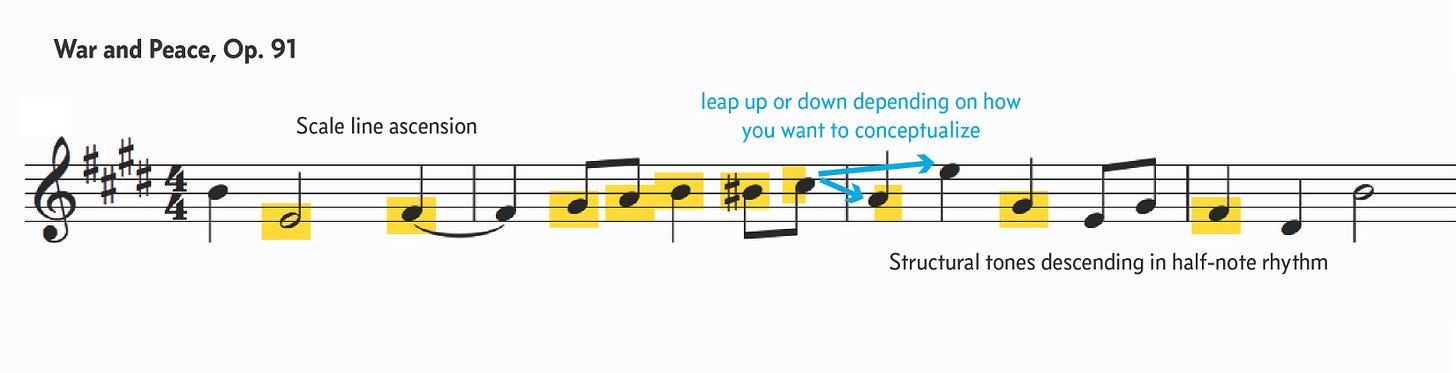

Straight up scale line melodies with one or two large leaps (larger than a third)

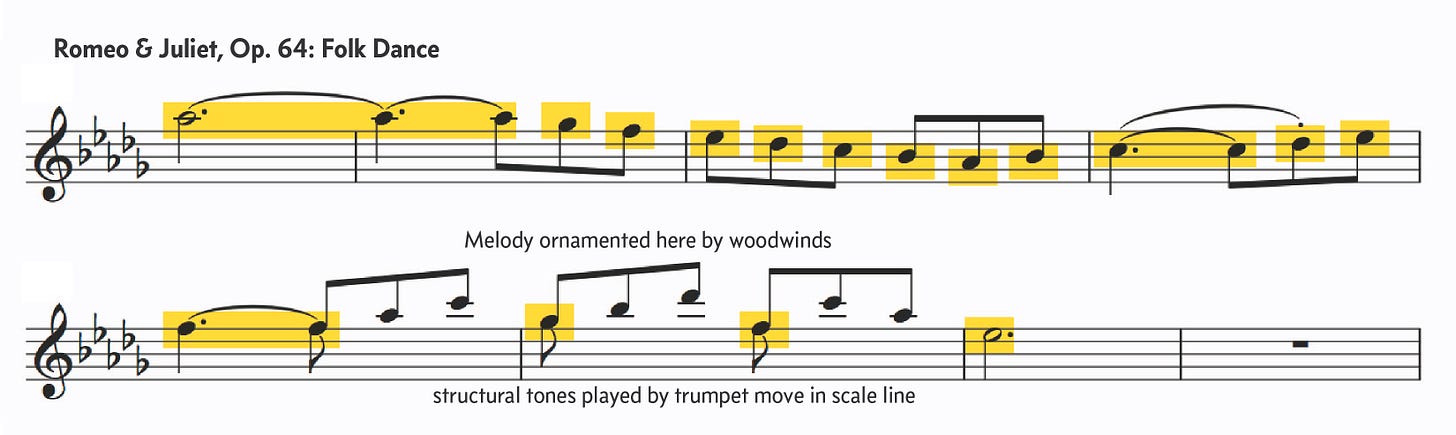

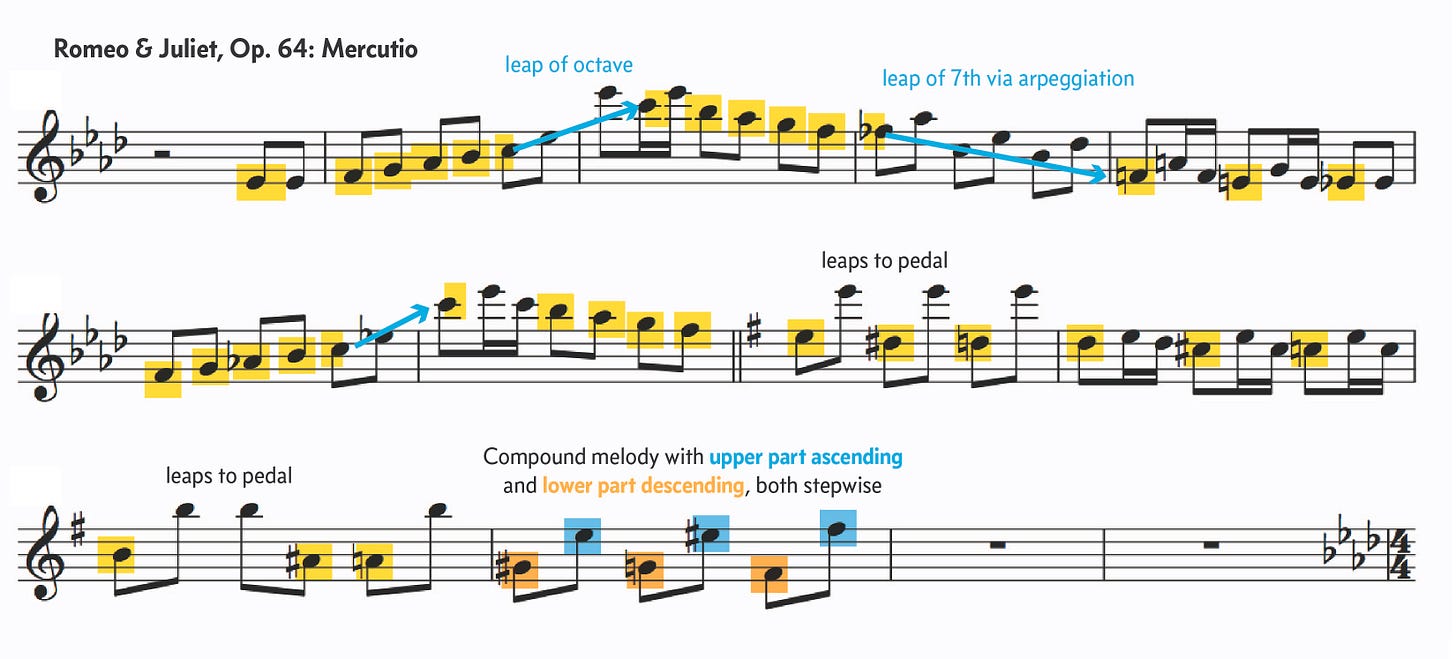

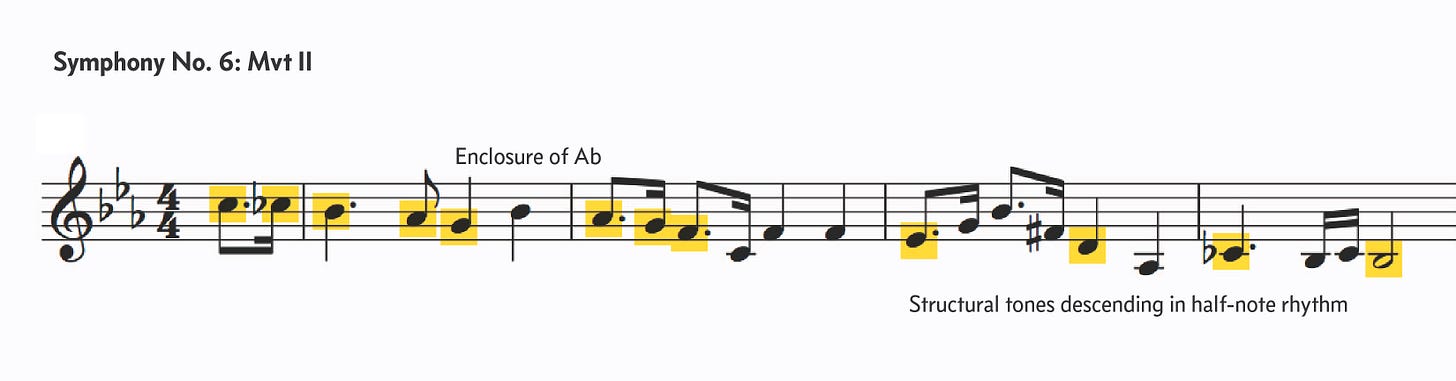

Melodies that have an overriding scalar (up or down) direction that is elaborated with arpeggiation and neighboring/enclosing tones but otherwise has a clearly discernible stepwise structure

Here are some examples of the first type:

And here are some examples of the second:

In creating these examples, I also noticed another pattern: many of Prokofiev’s melodies are a blend between these two types and tend to begin with literal scales and then about halfway through, ornamentation and embellishment pick up with the result that note to note, the melody is no longer following a scale; however, the architecture of the back half of the melody over all is usually structured atop an ascending or (more frequently) descending scale (see the excerpt from the 5th symphony, for example).

None of this is particularly groundbreaking, but it’s good to remember the power of scales to create a flowing, memorable line. Try writing a few scale line melodies with this recipe yourself. Pick a descending scale, start low, leap up early on, and make your way back down; or go with the opposite and pick an ascending scale, start high, hop down and work your way back up, applying ornamentation/enclosure/neighboring notes along the way.

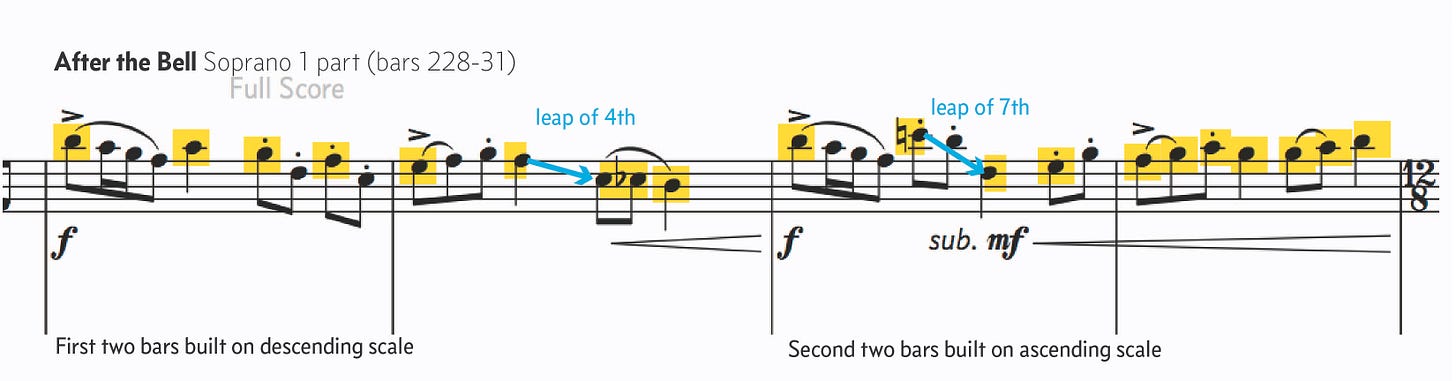

Here is my attempt at applying this, a melody I wrote for my saxophone octet After the Bell. I very consciously was thinking of how Prokofiev wrote some of his melodies, using the scale and a leap or two to structure the melody. My melody is not very Prokofiev-y, but I do find it to be effective and catchy!

Happy writing!