Golden ratios and bomb craters

Scene: Road tripping up the Columbia River Gorge with a couple of musical friends and the topic turns to Programmatic vs Absolute music - that is, music which is explicitly “about” something vs music that can stand alone, enjoyed without any explanation of what’s going on.

Well, actually… *I* started whining about not being able to write a piece titled Quartet No. 2, say nothing about what it was about, and then expect to have it taken seriously by potential performers and listeners.

My patient and more thoughtful interlocutors conceded that, while Quartet No. 2 probably wouldn’t automatically be a hit, there is a whole spectrum between a piece with an ambiguous title like that and the caricature of programmatic music I was painting—my caricature: music accompanied by text that is a play-by-play description of what’s going on in the music and what it means, e.g. “when the cymbal crashes, that is lightening striking the top of the mountain”.

I eventually came around to their point of view: adding just a bit of additional context to music, rather than distracting from and cheapening it, can create an entire layer of meaning that would be otherwise inaccessible to the listener.

’s evergreen observations from his book Show Your Work makes this point forcefully in a single drawing:By railing against programmatic music or music with a description, I was railing against a powerful tool for helping people connect with music and make meaning from it. And a powerful tool for providing people who could be interested in performing my music a compelling way in.

I also wasn’t being completely honest about my own writing process, which involves trying to get increasingly clear about what a musical piece I’m writing seems to be “about” and then iteratively editing it to get closer and closer, examining that north star occasionally to see if continuing in the same direction still makes sense.

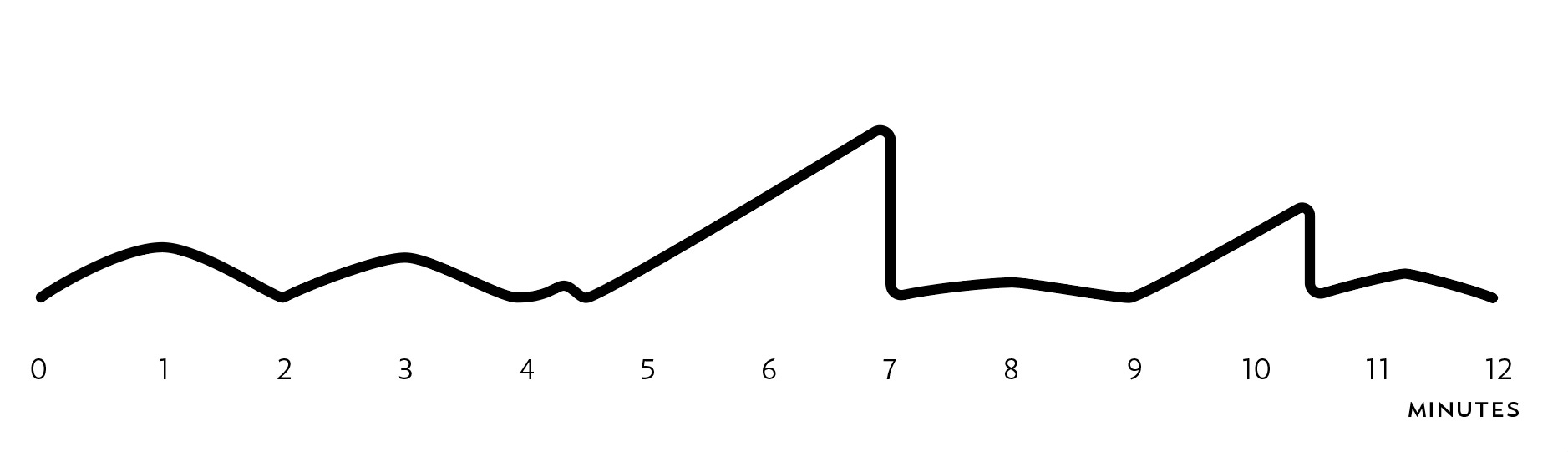

One of my friends in the car was on the hunt for new repertoire to perform next season. A couple weeks before our trip, I sent them a first draft of a piece I had sketched specifically with them in mind. I was encouraged that there was a lot they liked in the music, but they had a concern about energetic pacing in the music, which at the time could be represented as something like this:

The draft had placed a towering, frenetic climax smackdab in the middle of its run time. The music that followed the climax never really recovered the spirit or energy of what came before, existing very much in the shadow of the central crisis.

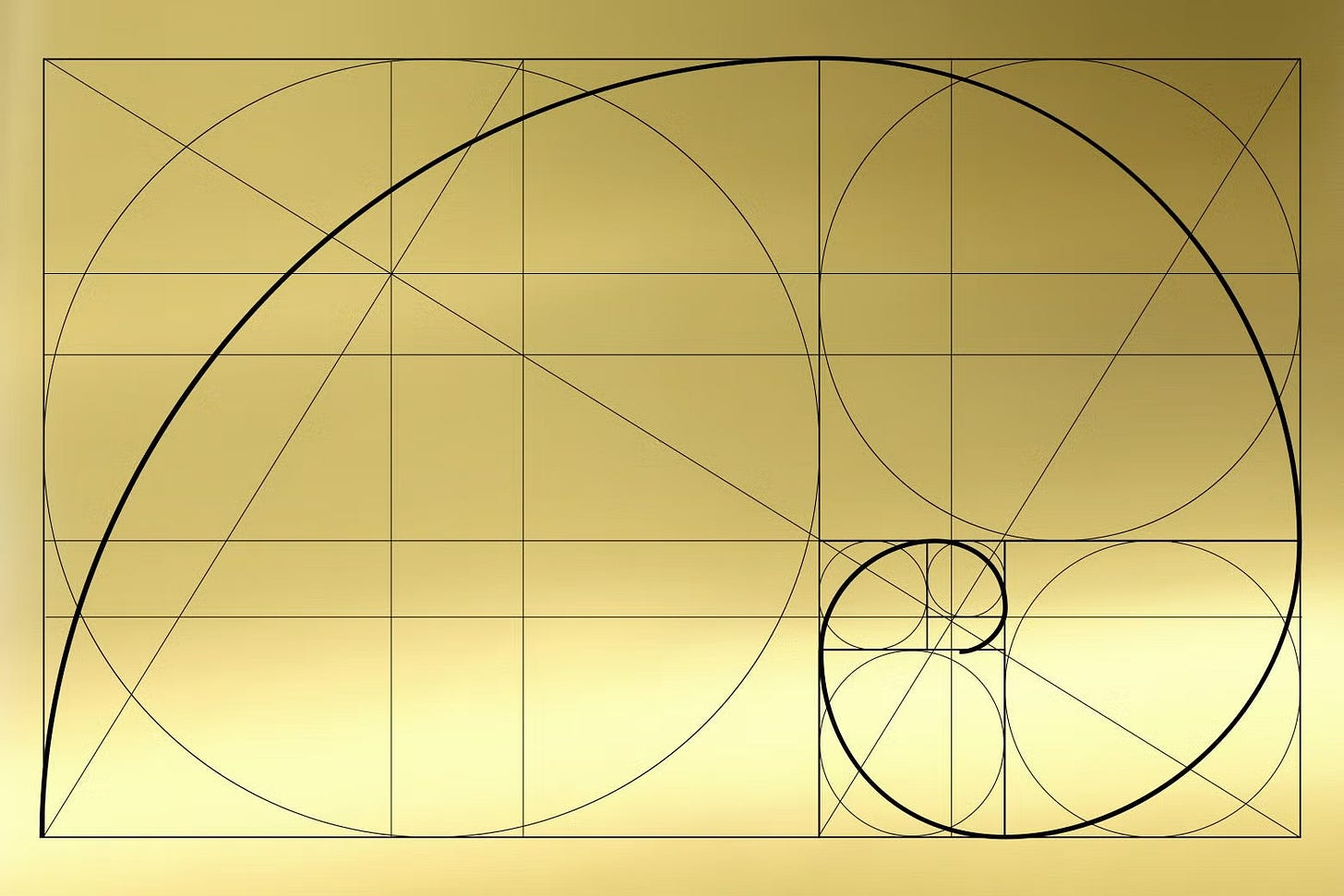

My friend was worried about the placement of this climax and that so much music followed it, worried that it dragged on unnecessarily and made the music dramatically flabby (my words, not theirs). They pointed to a well-worn and effective template for music/story writing/film, which is to place the largest climax right around 2/3 of the way through the music - a shorthand version of the golden ratio 1:1.618 or ~5/8.

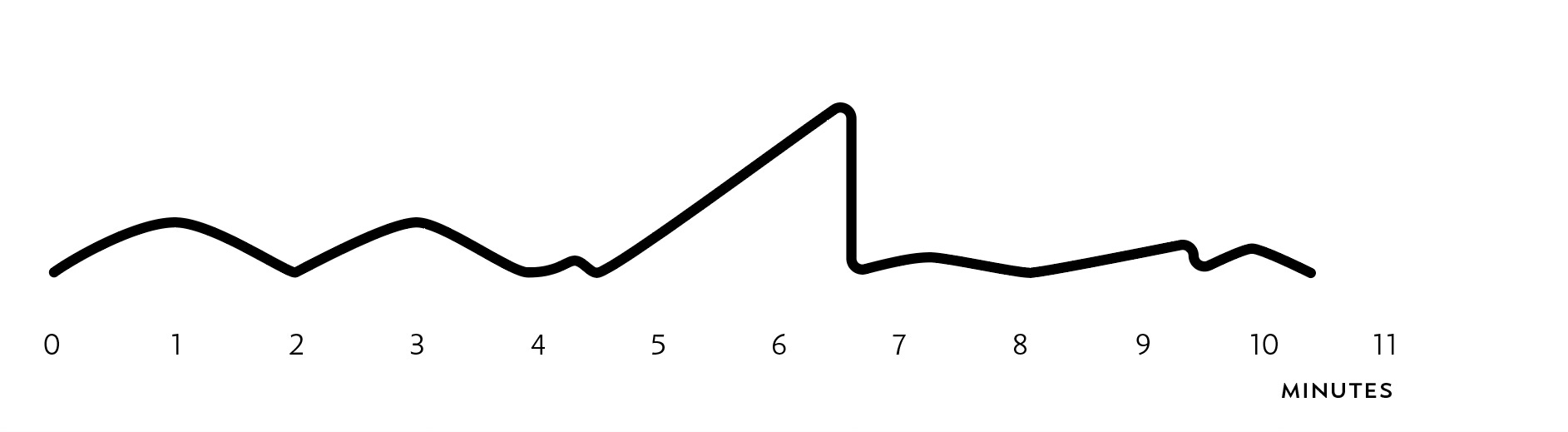

Encouraged that the music seemed compelling to my friend, I took their feedback and began revising the initial draft.

Following 17 revisions in two weeks, I still couldn’t find a way to make what I’d written adhere to those golden ratio proportions, unable to meaningfully change the proportions of the music or the placement of that central climax in a way that felt like it “worked”. (those 17 drafts were productive in many other ways - clarifying the music’s character and arc, giving a clear pacing to each section, and tightening up the orchestration). Through my editing, the lack of a musical high point at the characteristically climactic spot had become an even more prominent feature of the music than it was in the first draft!

What was going on?

I was trying to fit the music into a mold that wasn’t suited to what the music was “about”.

But I thought I wanted to write Absolute music, music that can stand on its own without listeners or performers needing to understand something beyond the sounds they were hearing to make sense of it?

Sometimes (usually) I don’t get to choose what my music is saying.

And the facts are that none of us approach music (listening or writing) without context: maybe we’ve heard of the singer or composer and are familiar with other things they’ve done; perhaps we have associations with the genre of music—bebop, country, classical—that create expectations for what we think we should be hearing.

My draft, written as a technical exercise in emulation, had outgrown the template and become music pointing to an extra-musical and universal experience: presence, loss, absence, and moving on. The big, shocked, musically numb hole right where the dramatic high point characteristically is is experienced like a bomb crater; clearly an important thing is supposed to be there and something happened to create that absence. That the cataclysm happens in the middle of the piece suggests the music is just as much about processing the disaster as it is about describing the events which precipitated it.

These are the kinds of programmatic thoughts that can help performers and listeners bring off and navigate a piece of music to sustain interest beyond where a purely musical experience might leave them.

It’s still on the composer to write something that “works”, that holds onto our attention from beginning to end, with or without that extra-musical elucidation. There’s so much program music—Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade, Strauss’ Alpine Sinfonie—that is marvelous to listen to without knowing a thing about the story behind the music—without knowing one recalls strolling through a gallery of your recently deceased friend’s artwork, another recounts a storyteller battling to save her own life with nothing but her stories, a third chronicles a somewhat ill-fated mountain climbing expedition. Knowing all of that can elevate the listener’s enjoyment of the experience and even, say, convince someone who wouldn’t otherwise go see their local orchestra to sit through the hour-long Alpine Sinfonie because they love the Alps and nature—subjects ravishingly represented in the Sinfonie.

A compelling dramatic arc is already clearly etched in my drafts. Creating a performer and audience expectation that the music traverses loss and absence—either in the title of the piece or in the program notes that introduce it—before they actually hear the music can help them contextualize the somewhat unusual structure of the music—a quiet, numb recitative flanked by two fierce climaxes.

I do tentatively have a title and program notes that provide this context. I’ll tease the music by leaving off with an excerpt of the program notes:

While this music recalls much of what matters and what is being lost—face-to-face connection with others, a non-utilitarian relationship to the natural world, seeing ourselves as part of that Something Larger which was here before us and will be here after us—the center of it is the hollow frenzy, overwhelm, horror, numbness, and dislocation that describes parts of modern existence today. As with the natural, physical, and digital worlds, the main idea of this music is packaged, repackaged, enhanced, sped up, piled upon, versions tossed aside with frightening frequency until cycles simply overlap and we find ourselves lost in the storm.

How do you feel about music that is “about” something vs music that makes no explicit reference to anything but itself?

All my compositions are “programmatic.” I am inspired to use music to express the thoughts and feelings I have about the world around me and thus allow listeners to experience those things in a new way. My listeners have expressed their appreciation for program notes and have frequently said that they help them have a greater understanding of and experience with the music. We are composing less and less for an audience well-versed in classical music. Programmatic music and program notes can help bridge that gap. I have gotten people who only listen to pop music enjoy extended techniques because of program notes.

One of the biggest things I miss about college is having friends to talk about things like this with. Too bad you're not on the east coast!